Since childhood and now as a father and designer, I’ve always loved engaging, exciting playgrounds.

In the early 1990s, there was one summertime destination my brothers and I would get excited about: my Great-Aunt Betty’s house. Not only were we excited to visit this sweet lady because of the pool in her backyard, but also because no trip to her house in Manheim, Pennsylvania was complete without a walk down the block to the Manheim playground. This timber playground was known as the O.U.R. Playground (Over-Under-Roundabout). At the time, it was the biggest playground in Central Pennsylvania and the first community-built timber playground in the area.

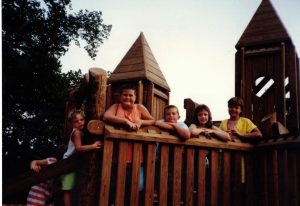

While it might have been a normal size to the grownups, its 2+ story towers, swinging bridges, platforms and stairs felt like a whole other world to us. I don’t remember what we would pretend as we went up, down and under seemingly hundreds of 8×8 wooden posts, but I do recall that we LOVED it. That playground was a castle one minute and something out of Super Mario Brothers the next. This playground unlocked hours of imaginative play for my brothers and me.

O.U.R. Playground, summer of 1991, Andy, brothers and cousins.

Places of Imagination and Discovery

My daughter investigating the Nature’s Play and Discovery Area.

Playgrounds are places where a child’s imagination can run wild. A simple play structure can become a fortress, a large boulder or change in elevation becomes a mountain, a sand box becomes a desert. The sky is never a limit when it comes to a child’s imagination. Utilizing natural materials, or new synthetic materials that appear natural but hold up to the rigors of play and environmental factors, provide children with a tactile and prescribed environment for play. Within a natural environment, children reap the benefits of biophilia, engaging with their surroundings in a tactile way. They also discover that everyday materials can be used in new, imaginative ways.

A great example of a natural play area constructed around biophilic principles can be found at the Ned Smith Center for Nature and Art in Millersburg, PA. Offering access to over 500 contiguous acres of forest, the center has a “Nature’s Play and Discovery Area” located adjacent to the primary buildings. This natural play area is filled with water features, a tree fort, rock wall, sensory pathway and more. These simple objects become vehicles for a child’s creativity and exercise the body and mind in a natural, intuitive way. The area is described as a “Yes” space: a space that gives children agency to explore all surfaces and spaces without boundaries.

Educare Chicago, a network of 25 birth-through-age-five schools, shares, “through imaginative play children learn critical thinking skills, how to follow simple directions, build expressive and receptive language, increase social skills and learn how manage their emotions.” When children step into the role of a pretend character, imaginative play can also build empathy and understanding of different people’s perspectives.

Places of Accomplishment

“I’m not sure if I can make it to the top.” That was the initial statement from my small but mighty 6-year-old daughter as she approached the central element of Liberty Green Park located in the East Liberty neighborhood of

Andy’s daughter in victory at the top!

Pittsburgh, PA. She followed it up with a quick, “But I want to.” The element in question was a two-story rope and net play area, and she was trying her hardest to work up the courage to scale it. Starting low and working through a couple of cells of the net matrix, she climbed higher and higher until she was at the top. From there, she was able to observe the entire park… and bask in the glow of accomplishing a task that initially she had not thought possible.

Rope and net play structures have increased in popularity in recent years. These elements look riskier to the casual observer due to their web of openings and holes. When interacted with, they provide an enhanced opportunity for hand-holds and support for even the most timid child, fostering a greater sense of accomplishment when the element is scaled. Nothing generates a bigger sense of self-pride than accomplishing a risky, difficult task. Within play area design culture, this is called this “Risky Play”. Risky play has substantial benefits across many aspects of children’s health, including their physical, mental, and social-emotional development.

Filling playgrounds and play structures with complex elements helps children learn how to navigate challenges. For example, faux rocks for bouldering are common sites on many playgrounds. These natural looking elements have hidden handholds and crevices which provide a sense of accomplishment when a child discovers and uses them to scale the boulder.

Dr. Suzanne Beno, Pediatric Emergency Medicine specialist and Medical Director for Trauma at The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto Ontario, describes the importance of risky outdoor play: “Physically, it increases activity levels and reduces sedentary time, contributing to lifelong physical literacy and possibly enhancing the immune system. Mentally, it supports resilience, problem-solving and conflict resolution, while socially, it fosters cooperation, communication and a sense of belonging.”

Places of Socialization

If you look around a busy playground, you’ll see children in constant movement and interaction with their peers. They may not have arrived together but even the shyest child will often socialize through play alongside others. Sometimes this socialization looks like a group of children breaking into teams for an impromptu game. Other times, it looks like a group of children talking side-by-side on swings. It could also be a younger child observing and mimicking older counterparts as they interact with a particular play element. By including a variety of equipment that supports large and small group interactions, these opportunities for socialization are encouraged.

A Buddy Bench at McCornack Elementary School, Oregon.

Socialization on playgrounds is so important that the concept of “Buddy Benches” has surged nationwide. Sandra Castellanos, a contributor for Edutopia shares, “How do we know when students are not being included during recess? Buddy benches create awareness and with awareness comes the responsibility to act.” Helping children identify a peer in need makes it a little bit easier to take the next step of reaching out. And all children appreciate knowing that their peers care about them.

Go Play!

One of my favorite playground examples is the Diana Memorial Playground at Kensington Gardens in England. This Peter Pan-themed playground is filled with spaces that delight a child’s (and adult’s) imagination, challenging structures made from natural materials, and an abundance of social opportunities for children of all ages. How cool!?!

“Play is foundational for bonding relationships and fostering tolerance. It’s where we learn to trust and where we learn about the rules of the game. Play increases creativity and resilience, and it’s all about the generation of diversity—diversity of interactions, diversity of behaviors, diversity of connections.” Isabel Behncke, a field ethologist and primatologist

The Diana Memorial Playground is designed on a scale that a child and a parent/caregiver can experience the play areas together.

You don’t have to travel to the United Kingdom to find engaging and challenging play environments. As a father, and playground fan, I have sought out playgrounds in the Central Pennsylvania region. In addition to the Ned Smith Center mentioned earlier, here are some of my favorites!

- The Tree House: Lititz Community Playground; Lititz, PA

- The Amos Herr Park; Landisville, PA

- Adventure Park; Hampden Township, PA

If you’re heading to western Pennsylvania, be sure to check out:

About the Author

Andy has served as a project architect for numerous public school projects. He has a positive track record for coordinating multi-disciplinary teams to work closely with each district to achieve design objectives following individual educational program goals and PDE requirements. His experience has led to a clear understanding of how well-conceived design can positively impact learning environments. He is an active member of A4LE and serves on the AIA Pennsylvania Education Subcommittee. When not working, Andy can frequently be found working on antique cars with his dad, “honking” with Harrisburg street band No Last Call, or taking part in his...

Learn More About Andrew